Gerald M. Best (1895 –

1985) grew up in

Port Jervis, New York, and was a Cornell Graduate in Electrical Engineering. He

worked for Warner Brothers as a sound engineer beginning his career just as

talking movies were being introduced.

Jerry, as his friends called him,

was a member of the Southern California Live Steamers during the early 1950’s. A

resident of Beverly Hills, he and his wife, Harriet, lived 7 blocks east of his

good friend Dick Jackson. Besides the fact that both of these men were involved

with railroad history, they both shared an interest in collecting steam

locomotive builder’s plates. Their collections were extensive and were finished

to museum quality. Although Jerry did build some miniature railroad equipment,

most people were more familiar with his full size sugar cane locomotive, the

“Olomana”.

In 1948, Jerry and fellow club member Ward Kimball

purchased two 3 foot gauge, nine ton, tank locomotives from the Waimanalo Sugar

Company in Oahu when the Hawaiian sugar plantation stopped using steam engines.

Both were built by Baldwin in 1883 to the same specifications. Jerry’s engine

was construction number 6753. They had 24 inch drivers, 7 by 10 inch cylinders

and were 0-4-2T Saddle Tank Engines with no rear bunkers for fuel. With only

short distances to run, the fuel was stored on the fireman’s side of the cab.

Ward’s locomotive was Number 2, the “Pokaa” (Poh-kah-ah), while Jerry’s was

Number 3. The name “Olomana” means “The Big Noise” in Hawaiian.

In 1948, Jerry and fellow club member Ward Kimball

purchased two 3 foot gauge, nine ton, tank locomotives from the Waimanalo Sugar

Company in Oahu when the Hawaiian sugar plantation stopped using steam engines.

Both were built by Baldwin in 1883 to the same specifications. Jerry’s engine

was construction number 6753. They had 24 inch drivers, 7 by 10 inch cylinders

and were 0-4-2T Saddle Tank Engines with no rear bunkers for fuel. With only

short distances to run, the fuel was stored on the fireman’s side of the cab.

Ward’s locomotive was Number 2, the “Pokaa” (Poh-kah-ah), while Jerry’s was

Number 3. The name “Olomana” means “The Big Noise” in Hawaiian.

Friend Chad

O’Connor helped to rebuild Jerry’s engine and he kept it at Ward’s Grizzly Flats

Railroad engine shed in San Gabriel, California. He would fire up the “Olomana”

on Grizzly Flats run days, filling the air with the smell of wood smoke. Ward’s

“Pokaa” underwent a more drastic change in appearance than Jerry’s, with the

removal of the saddle tank and being painted in 1880’s red and fancy polished

brass, while “Olomana” sported a more conservative dark green color. Ward’s

locomotive became the “Chloe”, named after his youngest daughter.

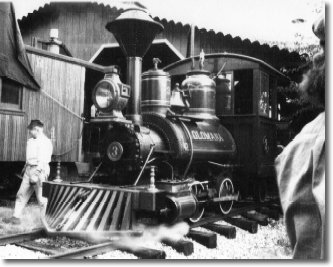

Jerry Best Walks behind “Olomana” after pulling her out of Ward Kimball’s

engine house for a run day in 1969. A tarp covers the cupola on Ward’s caboose

in background. Photograph taken by Harlan Hiney.

Jerry was one of the foremost railroad photographers and

helped many authors compile steam locomotive rosters for their books and

magazine articles. Also an author, Jerry wrote eleven books on railroad history

and Harlan Hiney was fortunate to do artwork for four of them. The first was in

1963 and was a pencil drawing for “Ships and Narrow Gauge Rails”, about the

Pacific Coast Railroad and Steamship Company. In 1969 Harlan did a casein

painting of the “Jupiter” for the cover of his book Iron Horses to Promontory,

portraying Stanford’s train enroute to the Golden Spike celebration. Jerry was

considered by many to be the foremost authority regarding the color scheme of

the Gold Spike Locomotives, enabling the creation of an historically accurate

painting.

Jerry was one of the foremost railroad photographers and

helped many authors compile steam locomotive rosters for their books and

magazine articles. Also an author, Jerry wrote eleven books on railroad history

and Harlan Hiney was fortunate to do artwork for four of them. The first was in

1963 and was a pencil drawing for “Ships and Narrow Gauge Rails”, about the

Pacific Coast Railroad and Steamship Company. In 1969 Harlan did a casein

painting of the “Jupiter” for the cover of his book Iron Horses to Promontory,

portraying Stanford’s train enroute to the Golden Spike celebration. Jerry was

considered by many to be the foremost authority regarding the color scheme of

the Gold Spike Locomotives, enabling the creation of an historically accurate

painting.

A year later Jerry suggested that Harlan create a painting

of the Union Pacific Number 119 to make a pair of lithographs to sell. By 1970,

Harlan’s 24 by 36 inch oil painting of the Number 119 along with the painting of

the Jupiter were made into 12 by 16 prints. They were sold though out the United

States in the 1970’s and at the new Museum in Promontory, Utah.

A year later Jerry suggested that Harlan create a painting

of the Union Pacific Number 119 to make a pair of lithographs to sell. By 1970,

Harlan’s 24 by 36 inch oil painting of the Number 119 along with the painting of

the Jupiter were made into 12 by 16 prints. They were sold though out the United

States in the 1970’s and at the new Museum in Promontory, Utah.

|

Gerald M. Best is a name well known in the Blue Book of

Railroad Historians. On the basis of his locomotive research, books and personal

participation in the great tradition of steam railroading. Best has long been

considered one of the nations leading authorities on the steam

locomotive. |

|

|

Gerald Best holds a replica of the Golden Spike in front of

the ex V and T locomotive “Inyo” that was painted to portray the “Jupiter”, as

part of Union Pacific’s exposition train in May of 1969. This photograph was

used on his book jacket, Iron Horses to Promontory. Photograph provided by

Golden West Books. |

In the early

1970’s, men from Disney’s mechanical department took measurements of “Olomana”

for a new railroad to run at Disney World’s Fort Wilderness Campground Resort.

While the new locomotive would be somewhat different than Jerry’s, the cylinders

and running gear would be identical. As Jerry told Harlan, they just sliced six

inches out of the center and made them to run on 30 inch gauge track. By 1973,

Disney had completed four 2-4-2T locomotives with a squared off saddle tank for

more water capacity. Each engine would pull a 5 car train of 4 wheel open sided

cars over a 3 ½ mile line. Unfortunately this venture had too many problems, and

after only four years was discontinued in 1977.

During the same

year, Jerry, then 82, decided to donate “Olomana” to a museum. Her home is now

the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. Before Jerry’s death in 1985, his extensive

collection of photographs, which included over 40,000 negatives, was donated to

the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.